TechDispatch #3/2025 - Digital Identity Wallets

The path towards a data protection by design and by default approach

1. Executive Summary

The idea behind a Digital Identity Wallet (DIW) is to provide users with an easy way to store their identity data and credentials in a digital repository. This enables them to access services in both the physical and digital worlds while ensuring accountability for transactions.

The purpose of this TechDispatch is to introduce the concept of a DIW, understand the privacy risks that exist when using a DIW, and discuss relevant data protection by design and by default requirements and their implementation, including relevant technologies. Eventually, we assess how the European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDIW), mandated by the eIDAS 2 Regulation, fits within the framework outlined.

In general, we can identify four main actors within an identity management ecosystem: the users of a DIW, identity and attribute providers (IdPs), relying parties (RPs) and the scheme authority. Depending on the governance schema, other actors can also play a role. Various digital identity models have been developed over time and are currently in use. These include the isolated model, the centralised model, the federated model and the decentralised model, depending on the architecture of the schema and on the role of the IdP. We describe these models and assess their respective pros and cons in Chapter 2.

In a user-centric identity paradigm, where credentials are stored under the user’s control, such as with a DIW, there is no need for the RP to access the IdP to verify the user’s credentials with each request. This mitigates the risk that an IdP profiles users by observing and linking their transactions with different RPs.

DIW solutions are typically implemented through a combination of mobile applications and cloud infrastructure, and can be used for identification and authorisation, as well as for issuing and using digital signatures. These solutions use digital credentials constructed and protected by cryptographic techniques, called ‘verifiable credentials’. Well-designed DIWs can provide easy access to public and private services, and enhance users’ control and privacy, convenience, interoperability and data security. This document identifies DIW functionalities and currently most-commonly deployed solutions to implement verifiable credentials in Chapter 3.

Unauthorised access to a user's DIW could reveal personal data, including sensitive information. Access to a user’s transactions, along with the ability to link them, would allow a party to create a profile of the user. The unfair and unlawful exploitation of user profiles could have prejudicial consequences for DIW users, including serious ones. This document mainly addresses DIW design choices that can mitigate these risks, focusing on the principles of data protection by design and by default. It is limited to risks relating to the integrity and confidentiality of the DIW, the risk of over-disclosure to relying parties, and the risk of linkability of DIW transactions, which could enable tracking and profiling. These risks and the relevant data protection requirements are described in Chapter 4.

Chapter 5 of the document then sets out measures to mitigate these three main risks. To mitigate risks to integrity and confidentiality, it refers to secure elements (SEs), which provide a physically separate secure environment, as well as to platform-specific trusted execution environments (TEEs), which are used to isolate cryptographic operations and store sensitive data. To mitigate the risks of over-disclosure and linkability, the document introduces anonymous credential technology, which enables authentication without identification in cases where identification is not strictly necessary. Although anonymous credentials are not a new concept, they have not yet been widely adopted. There are challenges to their use, yet new developments are emerging.

Finally, Chapter 6 is dedicated to the amended eIDAS Regulation. This Regulation provides for an EU-wide digital identity framework setting out rules for Member States to offer EUDIWs by the end of 2026. This document outlines the EUDIW and its features within the broader context of DIWs as described in previous chapters, and evaluates its potential to mitigate the aforementioned data protection risks.

1. Introduction

What is a digital identity?

In the past, if we had to file our tax return using non-digital means we would have had to visit the competent tax office and present our ID card or an equivalent identification document. Similarly, if we wanted to borrow an age-restricted publication from a library, we would have had to go to the library and again show our ID card to prove that we were old enough to borrow it.

Our daily lives are increasingly supported and shaped by the availability of the internet and of digital tools and resources. Mobile devices provide ubiquitous access to these resources. Nowadays it is possible to fill in and submit our tax return, or order and receive an age-restricted publication from the comfort of the beach or the sofa at home. In addition to an internet connection, these services require a digital method of proving our identity to the tax office and demonstrating authorisation to the library.

Therefore, we can think of our digital identity as a digitised version of our physical identity documents and other credentials. More broadly, we can think of our digital identity as the entire collection of our digital interactions. It includes any use of our connected devices, our browsing history and preferences, our presence on social networks, our digital payments etc.

If someone with no need to know had access to this broader representation of our digital identity, they would be able to learn and further infer ‘who we are’, with all the consequences and risks that this entails, which are recalled later in Chapter 4.

More specifically, the most common use of the term ‘digital identity’ refers to a collection of pieces of information about a person that facilitates interactions in the digital realm. We can refer to these pieces of information, usually called ‘attributes’, and present ‘claims’ about them (to access a resource or for an entity to verify our identity and status) in a trustworthy way and in a machine-readable and verifiable format. These claims take the form of ‘credentials’. The attributes are individual data fields within those credentials. These credentials, when constructed and protected by cryptographic techniques, have been often referred to as ‘attribute-based credentials’ and more generally as ‘verifiable credentials’[1]. In the following sections, we will use the simple term ‘credentials’ as a synonym for ‘verifiable credentials’[b].

The digital identity wallet concept

The idea behind the Digital Identity Wallet (DIW) concept is to create a digital repository for our identity data and credentials. This would work in a similar and analogous way to how we keep our physical ID cards, passports, driving licenses, or other cards and documents that enable us to access services (such as healthcare or car rentals) in a physical wallet. These identity data and credentials are personal data, as they relate to an identifiable natural person.

Often our personal data and credentials are scattered across different digital platforms, mostly under their control and managed with varying levels of trust and security. The DIW plans to bring our credentials and other personal data into one ‘place’ to manage them conveniently, securely and, as far as possible, under our control.

In principle, a DIW may go beyond identity information; depending on the information the user wishes to share through the DIW, it may also become a repository for all kinds of digital files and information that support our daily activities: from professional or education certificates to home utility contracts and bills; from a certificate of ownership of a house to a library card or a gym membership card; from a supermarket loyalty card to a leisure activity ticket. It could also act as a traditional wallet, holding and managing digital currency. We can think of this extended DIW concept as what is usually called a Personal Information Management System (PIMS)[2], storing and managing any kind of personal data.

One notable and influential DIW project is the European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDIW), an EU initiative that provides cross-border interoperable digital identity solutions within EU countries. Electronic identification solutions already exist or are being developed and integrated with the management of other documents and credentials, and are being harmonised as a EUDIW[3]. Many DIW solutions also exist worldwide[4] to access public and private services and digitally sign documents. Furthermore, some companies[5] provide identity management technical frameworks to build DIW based on decentralised identities[c] and pilots have been developed in research projects in recent years (see referenced literature).

Purpose and scope of this TechDispatch

The purpose of this TechDispatch is to introduce its readers to the concept of DIW and provide an analysis framework that can be used to assess a particular implementation. The document describes the role of DIWs for digital identification, authentication and authorisation in transactions, offering readers a perspective that will help them to better understand what privacy risks[d] exist when using a DIW. It also discusses relevant data protection by design and by default measures that could be implemented to mitigate such risks. Eventually, the document will assess how the EUDIW, mandated by the eIDAS 2 Regulation[6], fits within the framework outlined.

The assessment of data protection risks does not consider specific use cases, but rather refers to the ‘by design’ features of the DIW. The TechDispatch does not explore all dimensions and flavours of the DIW concept but rather introduces these matters with a view to supporting the discussion on the selected privacy and data protection risks and mitigating measures.

2. Digital identity management ecosystem and models and relevant privacy issues

Actors of the identity management ecosystem and terminology used

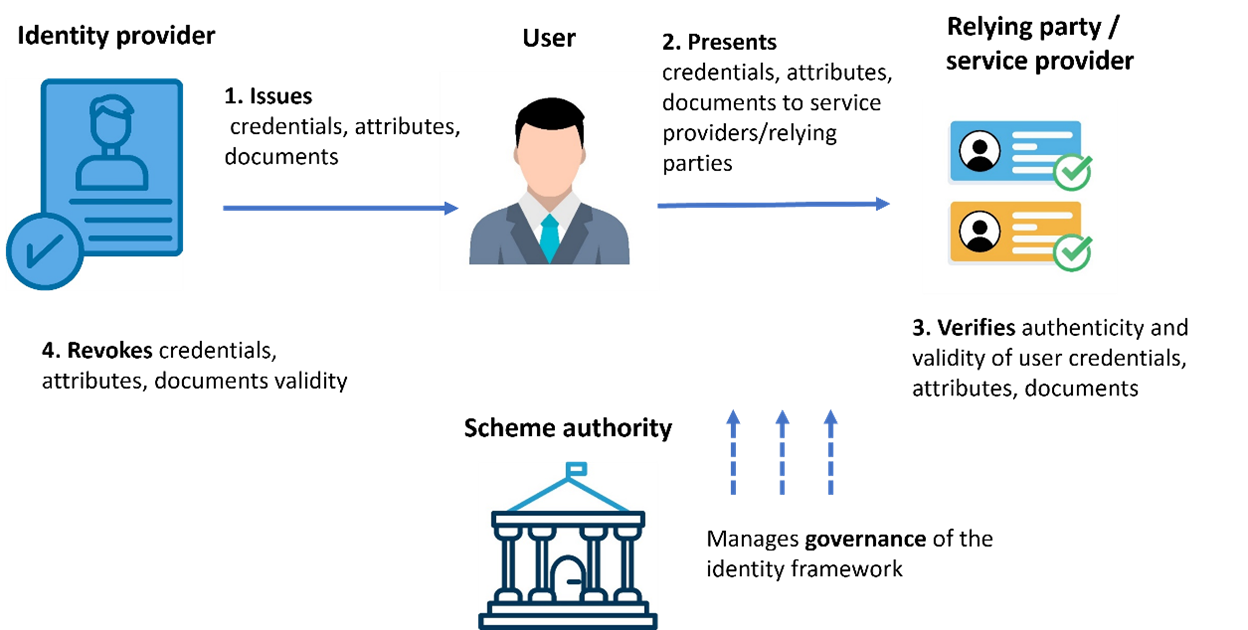

We can in general identify four main actors within the identity management ecosystem. We present what we consider a common terminology to identify these actors, but alternative names are also introduced.

- Relying parties (RPs) - They provide digital services to users (e.g. tax filing), which is why they are also called service providers (SPs) in the literature. Alternatively, they may need to verify the identity and/or credentials of wallet users for various reasons (e.g. a police officer verifying the authenticity and integrity of a driving licence). An RP may also be referred to as a ‘verifier’.

- Users who wish to access via digital means the services offered by service providers/relying parties or whose identity or credentials need to be verified by them. In particular, when using a DIW, a user may also be referred to as a ‘holder’.

- Identity and attribute providers (IdPs) - They provide users with the means (credentials) to authenticate themselves to, or to be authorised by, relying parties/service providers. They may also be referred to as ‘issuers’, since they are the entities that issue users’ credentials. Identity providers may be defined by law or by national authorities, or directly or indirectly by the community of the users and RPs based on the established governance of these communities.

- In addition, often IdPs take on the role of ‘revocation manager’, as they basically manage the entire credential lifecycle, including the revocation of the validity of credentials. The employment of credential validity periods and revocation can significantly reduce frauds caused by stolen and lost credentials.

- Scheme authority - A ‘competent authority’, usually appointed by law, to oversee the fair and lawful implementation of the framework, or an arbitration body that is commonly agreed upon or accepted by all the other actors. The role of the scheme authorities is to manage the governance of the framework for trusted and effective functioning. For example, national competent authorities exist for the EU Digital Identity Framework and the European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDIW). Describing the EUDIW framework role is out of the scope of this document. You can read the relevant referenced literature, as also recalled in Chapter 6.

Figure 1[7] - Example of interaction among actors in an identity management ecosystem

Other roles may be identified also based on how trust is managed among different actors or based on operational needs.

In principle, an identity management framework can also be designed so that a specific role for the IdP, as distinguished by the user, is completely excluded. Users can act as providers of their own identity, in which case the trust relationship between users and RPs/SPs would need to be established directly. We elaborate more on this option in the next section.

Digital identity models

Various digital identity models have been developed over time and are currently in use. In this section, we describe these models and assess their respective pros and cons, with a particular focus on the ability of the digital identity framework actors to track and profile users’ transactions.

The isolated identity model

A model widely used is the isolated identity model. Here the relying party/service provider (RP/SP) acts also as an identity provider (IdP). The user is given (or allowed to choose) certain credentials (e.g. user ID and password) at registration time, which are verified by the same RP at subsequent access requests. These credentials are exclusively linked to that specific RP (e.g. a flight booking website).

Main relevant considerations:

- The user has to manage separate credentials for each and every RP, which may be a burden and expose them to security breaches.

- Credentials remain with the RP, which in theory could misuse them or manage them insecurely, despite users generally having the opportunity to change their credentials if they so wish.

- On the other hand, transactions with different RPs have no connection among them by design, since each RP is also a separated IdP.

However, there is always a risk of linking different transactions if RPs collude with each other, enabling user profiling across different services. Or, if the user utilises the same credentials for different RPs (e.g. the same user ID and password for different websites), access to their credentials can anyhow give access to multiple services on behalf of the user.

The centralised identity model

In the centralised identity model, an identity provider (IdP) exists separately from service providers/relying parties (SPs/RPs). Users can register with an IdP once and use the same credentials issued by that IdP to access various RPs. There are various commercial examples of RPs that initially acted as an IdP for their own services in an ‘isolated model’, and now also act as a centralised IdP for other RPs that trust them.[8]

In this model, user credentials are stored within IdPs. In general, when authenticating against an RP, the latter redirects the user to the IdP, which verifies the credentials and provides the response to the RP.

Main relevant considerations:

- Increased usability with respect to the isolated model since the same credentials can be used to authenticate against various RPs (single-sign-on principle). Yet there could be some scalability concerns for the IdP.

- Credentials are no longer in the hands of the various RPs but are all in the hands of a unique entity. This reduces the attack surface for the credentials of a single user but the centralised IdP becomes a single point of failure from a functionality and security point of view, with the possible compromise of a large amount of user credentials.

- In case the credentials verification process by the RP entails a communication between the RP and the IdP, the centralisation of identity management enables the IdP to learn about all the transactions carried out by the same user (via the common credentials) with different RPs. This can enable the IdP to build a profile of these users, at least limited to those services relying on the specific IdP. Moreover, the user has no control over the data shared by the IdP to the RP.

The federated identity model

It is possible to design a federated identity model, based on a federated architecture of identity providers (IdP), where the credentials provided by one IdP are also recognised by RPs associated with other federated IdPs. This model leverages trust relationships among multiple domains and can bridge the incompatibility gap among many identity domains, each of which is supported by a different centralised identity management. A user may decide to use any of the IdPs of the federation to access an RP that is not natively served by that IdP.

Main relevant considerations:

- Further increased usability based on the single-sign-on principle.

- Scalability can be better managed by balancing (when it is possible) the various IdPs.

- In principle, credentials can be distributed among IdPs, offering the possibility to solve availability problems and mitigate the single point of failure problem of centralised IdPs. On the other hand, the overall security would depend on the weakest IdP (who could e.g. create false credentials for users from other IdPs).

- Along the same line of reasoning, breaking down a centralised model into many federated ones might mitigate (unless there is collusion among them) the user profiling risk.

The user-centric identity paradigm

The design of the aforementioned models implies that credentials are not under the user's control and can be used, though in different ways and at different levels, to track their transactions. Solutions have been proposed for users to store credentials issued by an IdP in a device or a digital infrastructure, to some extent under the user’s control, as part of a user-centric identity paradigm.

Main relevant considerations:

- Removing the need to access the IdP to verify the user’s credentials at each and every request of the RP mitigates the risk that the IdP could profile users by observing and linking the user’s transactions with different RPs.

- This model would also mitigate the risk of IdPs as honeypots for attacks against a treasure trove of credentials.

This model does not necessarily eliminate the need for the existence of an IdP as distinguished by the user. In user-centric solutions, IdP functions are, however, limited to the generation, issuance and revocation of the user credentials.

The Digital Identity Wallet is considered as the key element of a user-centric identity paradigm. Its features, advantages and risks are detailed in the next chapter.

The decentralised identity model and the concept of Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI)

The most meaningful interpretation of the expression ‘decentralised identity model’ is not so much the possibility of having multiple IdPs providing credentials to an EUDIW, but rather the one that aligns with the concept of Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI) and the absence of a single source of trust. The introduction of the concept of SSI represents a further step in the direction of user autonomy and independence from centralised IdPs[9]. The SSI concept focuses the user-centric paradigm on user autonomy in asserting and managing their identity. Christopher Allen proposed an SSI manifesto in 2016, featuring ten principles[10]. The SSI concept has been used and implemented with different meanings and interpretations[11]. Its original conceptualisation focuses on the total absence of a central provider of trust, often called the ‘root of trust’, with users potentially making ‘claims’ about themselves without relying on a central identity provider (e.g. the state and its trusted authorities). It is up to the relying parties involved to place confidence or not in the claims made by the users, based on the established and agreed mechanisms of trust. These mechanisms may be based on technology and organisation, for example leveraging cryptography and organisational rules, as in blockchain-based systems[12], or what is called the ‘web of trust’[13], a mechanism to build trust through a network of individual endorsements of cryptographic signatures of other users securely communicated via channels they mutually rely upon. To implement real-world use cases that require a high level of trust, such as in highly regulated domains like healthcare or finance, identity management frameworks based on the SSI model can be adapted to rely in some way on other commonly recognised roots of trust, such as those recognised by law. [14]

3. The Digital Identity Wallet: uses cases and features

This chapter outlines the use cases and high-level features of a Digital Identity Wallet (DIW). The next chapter then introduces more detail on data protection risks, requirements and risk-mitigating measures.

How a Digital Identity Wallet materialises in practice

Extensive research and pilot projects have identified the building blocks and features of DIWs.[15] However, DIWs have only recently begun to be deployed in real-world projects, mainly due to advancements in the security features and computational capacity of mobile devices, on which most of them are hosted. They range from solutions for managing publicly available digital identities to access public and private services (e.g. local public administration services, public health services, financial services and private banking services)[e] to identity management solutions for private and public closed user groups (e.g. university cards for authentication)[16].

DIW solutions are typically implemented through a combination of mobile applications and cloud infrastructure. Literature review and internet research on advertised solutions[17] indicates that mobile applications are the most common implementation approach. Mobile apps can feature user-friendly interfaces and mobile devices can embed secure hardware elements[f] to store credentials. In some applications, credentials may also be stored externally, such as in smart cards, and communicate with the mobile device via proximity technologies such as Near Field Communication (NFC).[18]

In other approaches, credentials and other data are stored in the cloud, where they are encrypted and the encryption key is managed in a way that even the cloud provider has no intelligible access to it. Cloud services are also used for complementary services to the wallet functionality, for example for credentials backup and synchronisation across devices, to timely propagate credential revocation, or to create interoperability bridges among different wallet implementations.

Some DIW projects leverage ledger technology and, more specifically, blockchain technology. Its permissioned[19] management model enables greater control, confidentiality and performance than a permissionless one. This model has been favoured in use cases where there is more need for centralised governance and regulatory compliance. In DIWs, the distributed ledger serves mainly as a decentralised registry for credential issuance and verification.

The Digital Identity Wallet use cases for identification, authorisation and digital signatures

Before asking for access to any resource or being verified, it is essential that the DIW possesses the relevant valid credentials. All identification data and other personal attributes the DIW requests from an IdP are signed[20] by a relevant IdP, thus ensuring their authenticity and integrity, and then issued to the DIW as credentials. They are then stored within the wallet in a secure way and presented to RPs when necessary.

It is then important to distinguish the concepts of identification (and authentication) from the concept of authorisation.

In some situations, we may be asked to prove our identity (i.e. to prove that we are who we claim we are) to access a service or because our identity needs verification, for example by a law enforcement officer. What is required of us is our identification, i.e. the disclosure of data (such as name, surname, date and place of birth, etc.) to uniquely identify us as a natural person in a way that is trusted by the RP. A DIW will contain all this information in an electronic, interoperable format and, as an indispensable feature, must give RPs reasonable assurance of the trustworthiness of that information. Another term we often see used for identification is authentication. More specifically, though, we can talk about authentication when the person, who has already identified themselves to the RP, needs to provide evidence of their identity.

For example, the first time we access a healthcare provider, its administration will ask for our identity data (our identification), which we may have in our DIW. The healthcare provider might then issue credentials that we can store in our DIW and use to authenticate ourselves whenever we use its services.

In other situations, we may need access to certain resources or services for which only an authorisation is required without the need to disclose our identity. For example, when we need to prove that we have the minimum age required to browse websites restricted to adults, or to be allowed as students to enter a university facility.

When the DIW holder wants to access the resource or the service, they present the required credentials to the RP, which verifies their authenticity and validity, including non-expiration, and, if the outcome is positive, grants the access.

In general, credentials released by the IdP are not forever and have an expiration date. The DIW or any RP might also ask the ‘revocation manager’ for a revocation if they believe credentials have been compromised. In this case, the DIW will need the IdP to issue new valid credentials to access again the resource or the service.

A DIW can also create a digital signature on behalf of a user by using cryptographic material (specific files with content and format suitable to cryptographic applications), such as digital certificates, signed and provided by an IdP and stored in the DIW. The DIW generates a pair of cryptographic keys[21]: a private key, which is kept secret by the signer and stored securely in the wallet, and a public key, which is shared with others to verify the signature. If a user wants to sign a document, this can be done either within the wallet, without exposing these sensitive cryptographic elements to external applications, or via an external service after providing it with the necessary authorisation in a secure way.

Potential advantages of well-designed Digital Identity Wallets

Well-designed DIWs can represent means to enhance user’s control, privacy and data security, as well as convenience and interoperability.

A DIW should integrate features to enhance user control over the personal information contained therein. DIWs would typically provide a dashboard to verify dynamically the status of their data and credentials, for example in the case of a wallet containing tickets for public transport. Furthermore, users would be able to monitor what attributes or credentials the RP requires access to and would be able to decide whether and what to disclose to the RP. Then, if the identity management framework provides for it, the wallet might be able to verify whether the RP is entitled (by the scheme authority) to even ask for these attributes. Ultimately, if this fits the specific use case, users may be able to decide the value of certain of their DIW attributes, such as user preferences for user consent management or to specify dietary requirements for online food shops. This may not be the case, for example, when the law stipulates that specific IdPs must issue legally valid identification data for identity cards and certain travel documents (e.g. passports).

Many identity wallet solutions incorporate hardware-based security elements, providing stronger security protection for user credentials compared to more traditional storage technology using only general-purpose hardware (see section 4.1).

Both these advantages of enhanced user control and security can provide a good basis for a better privacy protection of DIW users. A more complete assessment of personal data protection impact of DIWs and of the relevant mitigating measures is provided in the next chapter.

DIWs can provide more user friendliness in accessing digital services. They can enable users to store multiple identity credentials in one location always at hand and authenticate to or get authorisation from multiple service providers. This eliminates the need to remember and manage credentials in a separate way for different service providers. The information stored in the DIW can be used to register to different services online and provide the needed information without re-entering the same info once again for each service.

DIWs can be designed as an element of an overall interoperable identification scheme to provide interoperability amongst many IdPs and RPs, including across different countries. This implies consensus among all participant actors and an overarching policy and technical agreement managed by a scheme authority, as well as the adoption of standards and common protocols, in particular for the issuance and management of credentials and of the authentication/authorisation of DIWs against RPs.

Currently deployed technology frameworks for (verifiable) credentials

The use of verifiable credentials requires technological frameworks, supported by a governance structure and relevant rules agreed by all the participants in the ecosystem. These frameworks are made up of trust models/assumptions, cryptographic primitives, protocols and data formats. They have been developed over the years, with some of them becoming standardised. They have been designed to provide the functionalities needed to build trust among the stakeholders of the identity management ecosystem (see section 2.1). These functionalities include:

- the trustworthy issuance of credentials from IdPs;

- the binding of credentials to a user and a DIW device owned by that user (see section 5.1);

- the trustworthy presentation of credentials to and their verification by RPs;

- the revocation of credentials.

The variety of deployed solutions affects all layers of the technical architecture. Here, we mention a couple of examples of sets of protocols, emphasising the specifications of the format of verifiable credentials and their interface protocols, particularly those used to verify their authenticity and integrity. Further information can be found in the literature.[22]

Various solutions have been identified to implement verifiable credentials. Among those currently most deployed, we refer here to the one based on the so-called mobile driving license ISO/IEC 18013 family of standards. These standards have been conceived to define the technical and operational requirements for digital mobile driving licenses but are now being adopted in other use cases. They were born in proximity verification use cases (e.g. with a verifier communicating to the user’s mobile device through an NFC protocol) and aim to define a full solution, including protocols, data formats and security measures. The most famous standard of the family is ISO/IEC 18013-5[23], which defines, among others, a credentials data format, called ‘mdoc’, and the interface against the credentials verifier (the RP). A new standard of the family issued in 2024 (ISO/IEC 18013-7) extends the use of this protocol, originally born for proximity cases, for remote presentation of credentials over the internet.

Another set of solutions used and currently further developed is the one defined by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). They include the W3C Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs)[24] and the W3C Verifiable Credentials (W3C VCs)[25], as well as other standards for data authenticity and integrity. In particular, the W3C VCs defines a general-purpose data model for verifiable credentials and mandates to choose cryptographic primitives enabling privacy friendly features[g]. It also contains a rich non-normative text that is very useful to those seeking to develop an in-depth understanding of the verifiable credentials and identity management ecosystem, with a wide section on relevant privacy concerns. While the W3C had originally issued only a data format standard, the latest release of standards goes in the direction of providing a more complete suite of solutions by also proposing specific signature algorithms[26].

4. Data protection requirements and risks

Digital Identify Wallets (DIWs) are used to identify, authenticate and authorise users against RPs, performing many transactions over time. Unauthorised access to a user’s DIW could reveal personal data, including sensitive information. Access to a user’s transactions and the ability to link them would enable a party to learn about the user’s choices, behaviour and actions. They could then draw inferences from this information and build an even richer user profile. This would significantly interfere with the user’s private life and pose a high risk to their fundamental rights. Unfair and unlawful exploitation of user profiles can have prejudicial consequences for DIW users, including serious ones. This has a greater impact in situations where the DIW is used widely, such as when it is mandatory by law for certain use cases.

In this document, we will mainly address the design choices of DIWs that can mitigate risks, focusing on the principles of data protection by design and by default. However, we will not perform a full analysis of the risks to people’s fundamental rights, nor a complete analysis of compliance with applicable data protection laws and their principles.

We limit ourselves to the following risks (and related data protection requirements):

- risk to integrity and confidentiality of the DIW

- risk of over-disclosure towards relying parties

- risk of linkability of the DIW transactions, enabling tracking and profiling

Risk to integrity and confidentiality of the Digital Identity Wallet

The GDPR’s integrity and confidentiality principle provides that personal data should be processed “in a manner that ensures appropriate security”.[27] In this section, we consider the security risks and requirements for DIWs. The security of the credentials managed by the DIW also depends on the security of its interactions with other identity management framework actors, particularly IdPs for issuing and revoking credentials, and RPs for accessing DIW data. In this section, we focus solely on the security of the wallet itself.

Storing sensitive personal information within a single entity (the DIW) rather than with several service providers may increase an individual’s risk if relevant security measures fail. This is particularly true when personal data is stored on a specific user’s mobile device, and it could be even riskier in cloud-based DIWs, where the same cloud service provider may store the data of many users.

However, mobile devices offer a large attack surface due to the DIW app’s integration with the device’s operating system and other apps. Hackers could exploit these vulnerabilities to access the DIW. Furthermore, the security of mobile devices also relies heavily on the user owning them, and often depends on their awareness, skills and context.

For example, hackers could exploit security weaknesses in mobile apps or malware to gain system-level access and then exfiltrate or modify DIW data. Also, if a mobile device without access protection is lost or stolen and the DIW app is not protected by robust authentication, an individual in physical possession of the device could impersonate the DIW owner.

Risk of over-disclosure towards relying parties

The GDPR principle of data minimisation provides that personal data shall be “adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which they are processed”.[28] This is also known as the necessity and proportionality principle.

As previously discussed, the DIW is designed to enable users to manage their own personal credentials and other data. Users can disclose this information to RPs either to access a resource or to allow them to verify certain credentials. However, this functionality carries a risk of unintended over-disclosure of personal data[29], which goes against the principle of data minimisation. DIWs facilitate seamless interaction with digital service providers, but this carries a greater risk of unintentional and imperceptible disclosure of personal data than providing paper documents or manually filling in electronic forms. This is particularly pertinent when we consider the sensitivity and wide range of personal data that a DIW can store. This risk is also increased by a propensity of certain relying parties towards over-asking (requesting more personal data than needed).

The data minimisation principle implies that a DIW user should be able to securely disclose to an RP only the pieces of information necessary for the processing of personal data by that RP, for which the user has given consent or exercised the expected control.

The requirement enabling a DIW to present to an RP only a subset of attributes within the given credentials is called ‘selective disclosure’.[30] If, for example, the DIW credentials refer to a user’s national identification attribute alongside other attributes and if the RP only needs to know the user’s nationality, the DIW must be able to display only the user’s nationality without revealing all the other attributes. Another use case is age verification, whereby an RP verifies that a user is an adult or is above a certain minimum age or within an age range. In this case, it is unnecessary to disclose the user’s date of birth contained within the identification data. It is sufficient to disclose an attribute, issued by an IdP and trusted by the RP, or a value calculated based on the user’s birthdate, which shows that the user is within that age range.

Furthermore, selective disclosure implies that there should be a way to share credentials enabling authorisation without identification (often in literature also called ‘anonymous authentication’), when identification is not a necessary element of the processing of personal data, based on its established lawful purposes. In the nationality or age verification cases, for example, we have seen how it is not necessary to disclose the identity of the DIW user. Similarly, it is not necessary to disclose the identity of a user when verifying a theatre ticket stored in their DIW. Likewise, it is not necessary to reveal the identity of a driver when verifying a driving licence in their DIW, unless the outcome of the verification process has consequences for the driver that might require their identification (e.g. a legal fine). Also, service providers often require users to create an account and provide personal information that is not strictly necessary for accessing certain services.

Authorisation without identification mitigates[h] (or even avoids) the risk of unnecessary identifiability of the user of the DIW and thus any further tracking and profiling.

Risk of linkability of transactions, enabling tracking and profiling

The data minimisation principle implies also that the different user transactions should not be linked together (unlinkability), unless this is a necessary element of the processing of personal data, based on its established lawful purposes

The risk of linkability (and thus of identifiability and profiling) exists when the management of credentials, from their issuing from IdPs to their presentation to RPs and their possible revocation, entails the use of unique identifiers for a specific user among different transactions. Credentials provided by IdPs in traditional authentication/authorisation protocols usually contain those unique identifiers.

IdPs and RPs might keep track of all the interactions of the DIW with RPs and be able to build a profile based on the DIW transactions.

For example, IdPs under the control of government authorities or private companies could gather information about the habits and behaviours of any individual using a DIW when accessing online or proximity services or whenever their identity or attributes are verified by an RP.

In certain circumstances, it may be necessary to establish a link between transactions. For instance, competent authorities conducting anti-fraud activities may need to link transactions by the same DIW user to verify suspicious activity. In this case, this should be carried out without identifying the user. Identification would then only be needed in those situations where it is required to further investigate potential fraud. Conversely, when verifying the validity of a transport ticket, it is generally not necessary for the verifier to link different checks performed on the same user.

The unlinkability requirement contributes to implement the data minimisation and purpose limitation principles and mitigates the risk of identifiability of the DIW user.

In a digital identity framework, we can consider various DIW unlinkability requirements.[31]

- Unlinkability with respect to RPs

If a DIW presents their credentials to an RP on multiple occasions, that RP should not be able to determine whether these transactions correspond to the same user or a different one. The same principle applies when a DIW presents their credentials to several RPs, even if they collude and share the data they obtain from the DIW.

If there is a lawful reason to link many transactions of the same DIW, the principle of data minimisation also applies. This implies that only the data necessary for processing (i.e. connecting two transactions) should be disclosed beyond the credentials presented by the DIW.

- Unlinkability with respect to IdPs

The IdP should not learn about DIW transactions, i.e. what credentials a DIW presents to what RP and when. This kind of unlinkability is sometimes referred to as ‘unobservability’ of the DIW transactions by the IdP.

As we saw in section 2.2, moving to a user-centric architecture where a DIW can store credentials issued by an IdP eliminates the need to consult the IdP every time an RP needs access to them. Consequently, this DIW feature mitigates this particular risk of direct linkability by the IdP by design. See, though, the next two risks for a complete picture on IdPs.

- Unlinkability with respect to revocation managers

We also need to consider the unlinkability of DIW transactions against 'revocation managers' (IdPs or other entities acting as custodians of credential status). When RPs verify the revocation status of DIW credentials against a revocation manager, the latter could learn which RPs the DIW interacts with and when.

- Unlinkability with respect to colluding IdPs and RPs

This requirement considers the possibility that IdPs and RPs collude and exchange the information they know about the DIW, its credentials and transactions. Even in this case, it is important that DIW transactions could not be linked among them.

5. Mitigating measures for the selected data protection risks

Ensuring integrity and confidentiality

To ensure the integrity and confidentiality of the Digital Identify Wallet (DIW), robust encryption is essential when managing sensitive data such as credentials, regardless of the infrastructure storing them (e.g. mobile device or cloud). Strong end-to-end encryption is required when this data needs to be transferred to ensure that it remains unreadable even if it is intercepted. All this without forgetting the need to stand future quantum-based attacks via post-quantum cryptography.

Integrating separate hardware components and implementing a higher level of segregation for critical use cases, including key management, provides greater protection than mobile devices’ general-purpose hardware and operating systems, or general-purpose cloud infrastructures.[32] This is why DIWs should be deployed in devices that contain dedicated secure elements (SEs), which provide a physically separate secure environment, and/or platform-specific trusted execution environments (TEEs) for isolating cryptographic operations and sensitive data storage.

An SE contains a microprocessor chip engineered in a way that can store sensitive data and perform critical operations while offering lower exposure to threats. It acts as a vault, protecting the applications and data from typical malware attacks on the host operating system. Examples of secure elements for mobile devices include external hardware devices specifically designed for cryptographic operations, such as security tokens or smart ID cards. Secure elements such as SIMs, embedded SIMs (eSIMs) and embedded secure elements (eSEs) can also be integrated within the mobile device’s architecture. Current versions of mobile operating systems offer APIs to support operations with SEs, including embedded ones.

A TEE is an isolated environment within a device’s main processor[33] designed to protect sensitive operations and data from the rest of the device processing components, including the operating system and other applications. Often TEEs are used in combination with SEs, and some authors use the term TEE as already encompassing the integrated solution.

In cloud infrastructures, the solution may be provided by an isolated environment supported by dedicated hardened servers.[34] Hardware Secure Modules (HSMs) and other secure elements can also be deployed within a cloud infrastructure and connected to servers. A cloud-based architecture can relieve the mobile device of the burden of security management, enabling features such as credential recovery in the event of a lost device. However, it can present challenges in terms of availability and use in an offline context, where the device is not connected to the internet and proximity-based protocols are used instead.

In a DIW-based framework, it is essential to ensure that credentials are tied to the DIW device that requests their issuance or verification. This prevents credentials from being transferred to unauthorised devices, thereby protecting against theft or cloning. This feature is called ‘device binding’. A high level of assurance can be achieved by cryptographically linking a device's public key to a private key stored in a secure element of the device.

Of course, the overall security level of the solution as well as the final binding of the DIW credentials to the user, is strongly determined by the user’s access control to the mobile device and its functionalities. This should feature strong multi-factor authentication, including secure biometrics.

Overall, DIWs are intended to provide effective security measures, particularly for use cases requiring a high level of trust (e.g. government identification, law enforcement, border control and health services). This level of trust maybe set by specific regulatory security requirements, which can also provide for a mandatory certification as is the case for the European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDIW) (see section 6.3).

Even DIWs supported by the above solutions may have potential security weaknesses.

Firstly, users are responsible for managing the security of the mobile device on which the DIW data is stored. They may prioritise usability over a high level of access control; for example, they may not enable multi-factor strong authentication if the DIW application does not make it mandatory for the given use case.

While the embedded SEs of many current mobile devices provide strong security guarantees, their cryptographic functionality is often limited (e.g. storing cryptographic keys and performing some standardised operations to create digital signatures), which is insufficient to mitigate certain risks associated with the use of DIWs (see section 5.2)[35]. This means that changes to the current SE design by mobile manufacturers, as well as changes to the supporting operating system functionalities, would be necessary. However, these changes could not be implemented in the short term, particularly for lower-cost devices.

For this reason, many implementations rely on trusted execution environments (TEEs) rather than the full hardware-based protection provided by secure elements (SEs). However, research has demonstrated[36] that if these environments are not correctly designed, they may remain vulnerable to side-channel attacks and weaknesses in the TEE architecture and software implementation that could compromise sensitive credential data.

Selective disclosure and unlinkability: the case for anonymous credentials

The evolution of the internet has prioritised functionality and resilience over security and privacy. In particular, although the identification and development of privacy-enhancing protocols has a long history in research projects and pilots, it has not yet received adequate follow-up in standardisation, and the deployment of solutions in real-world scenarios is limited.

Relevant literature identifies the origin of privacy-preserving solutions for authentication in the foundational work of cryptographer David Chaum. [37] These solutions began to be developed further in the early 2000s and have been widely explored in research, with a further boost in recent years due to DIW projects, particularly the EUDIW.

High-level concept and features of anonymous credentials

This family of privacy-preserving solutions for authentication can be referred to as ‘anonymous credentials’, given their focus on their privacy-oriented design and features. These mechanisms support both selective disclosure[38] and the unlinkability requirements mentioned above. In this context, the term ‘anonymous’ refers to the ability to provide authentication without identification and to minimise data disclosure. Whether a user remains anonymous depends on the wider context[39].

Anonymous credentials are based on the use of advanced cryptographic techniques[40] whose purpose is to provide mathematical proof of a claim (e.g. the authenticity of a document and its origin), without disclosing any additional information. Rather than delving into the complexities of cryptography, we will provide a high-level overview of the concept of anonymous credentials.[41] Further information can be found in the reference literature.

The following text provides a simplified account of how anonymous credentials work within the simple identification framework described in section 2.1.

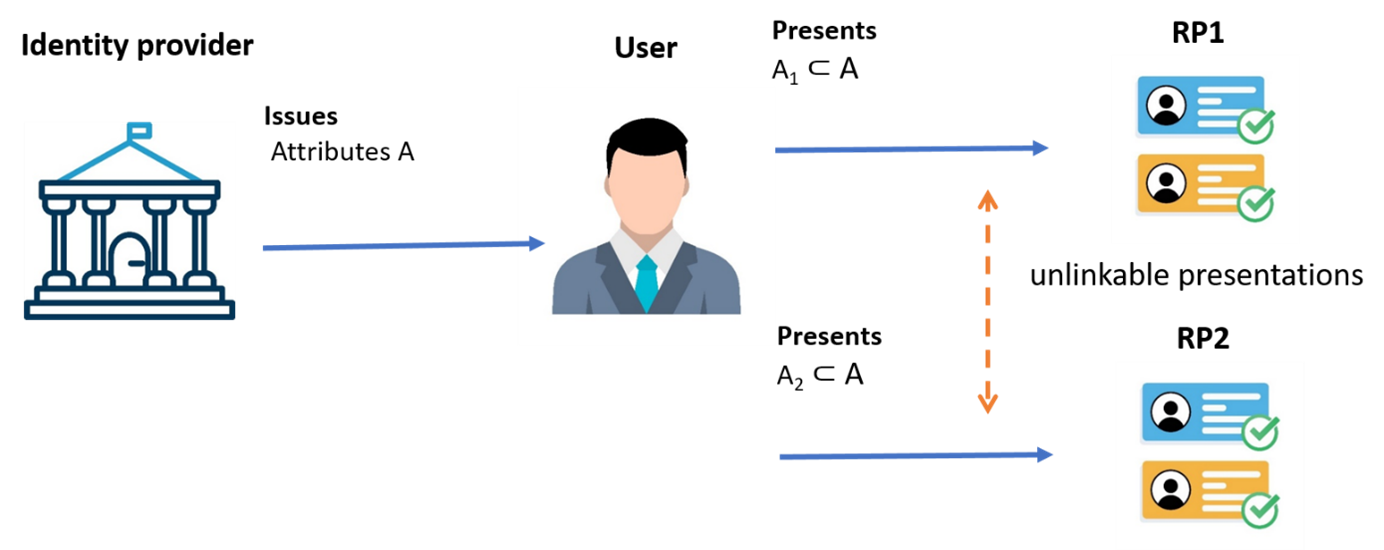

Figure 2, inspired by Slamaning, D. (2025)

We consider a user who has been given a certified credential by an IdP, attesting to the authenticity of certain user attributes (set A in figure 2). These attributes and credentials can be stored in a DIW. These attributes could include, for example, the information fields of an ID document issued by a public authority, as well as any other attributes that the public authority may certify. The credentials can be viewed as the relevant IdP’s digital signature on these attributes. When the user needs to show one or more attributes (subset A1) to an RP1, the anonymous credential provides the DIW with a disclosure protocol that enables the DIW to reveal only a subset of the attributes issued by the IdP (e.g. date of birth) or calculations made on them (e.g. whether the age is within a certain range). Similarly, the same user can disclose other attributes (e.g. nationality) (subset A2) to another RP (RP2) that requires only those attributes. This protocol assures the RPs that they are interacting with a user/DIW that has a valid credential from the issuer for the subset of attributes disclosed to them. This example can be successfully extended to multiple IdPs and multiple credentials within a DIW. Different presentations of credentials from the same DIW do not share any unique identifiers among them, let alone the user identity. This ensures that these presentations cannot be linked to each other, and thus that DIW transactions cannot be linked either.

Anonymous credentials may have many other useful features, some of which are not unique to this type of credentials. Some among the most peculiar and critical:

- Non-transferability - To prevent credentials from being unlawfully copied or stolen and used by another DIW, or even by an RP to which they are presented. As seen in section 5.1, the credentials are bound to the user and its device using a secure feature linked to the hardware when signing them (typically the public key of a key pair, where the private key is securely stored in the device) and biometrics are used for strong user authentication to prevent the device from being used successfully by other individuals (e.g. family members or hackers).

- Issuer-hiding - In certain circumstances, it may be critical for privacy reasons to reveal which IdP issued the credentials. Furthermore, disclosing multiple credentials from multiple issuers may also reveal information.[42] Rather than revealing the specific issuer, the user could instead demonstrate that they meet an ‘issuer policy’ accepted by the verifier — for example, the membership to a trusted set of issuers.

- Trustful pseudonyms generation - In case it is necessary to link transactions belonging to the same users without the need to identify them, it is possible to generate a pseudonym to be disclosed to the RP without revealing any static permanent identifiers. The pseudonyms, chosen by the DIW, not permanent and context based, would avoid identification and profiling when not needed. It could be construed starting from a unique identifier within the credentials and other parameters specific to the use case or categories of use cases, as well as parameters characterising the RP.

Cryptographic algorithms for anonymous credentials[i].

While they all satisfy the unlinkability requirements, one distinction can be made as to whether the signed attributes are disclosed to the RP, or whether only a ‘predicate’ (a statement) based on those attributes is disclosed. If a DIW wants to provide a trusted statement to an RP based on its attributes without revealing their value, it can offer a ‘zero-knowledge proof’ (ZKP)[43] based on those values. For example, if a user wants to prove that they are within a certain age range, they can provide an RP with a ZKP based on their date of birth without disclosing it.

Anonymous credentials can be designed using specific types of cryptographic signature schemes that are computationally efficient and can be used proficiently to build zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs). Among these signatures, we mention Camenisch-Lysyanskaya (CL) ones[44] and BBS/BBS+ ones[45]. Anonymous credentials can also be built based on any signature scheme, such as the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA)[46] or a non-interactive zero-knowledge (NIZK) proof system[47]. Although difficult to implement in practice due to computational challenges, recent proposals claim an easier use of generic signatures for anonymous credentials, thus enabling the creation of ZKPs from credentials signed with any signature and digital identity scheme[48]. This could facilitate the practical adoption of these credentials.

Deployment status and challenges

Anonymous credentials in all their different algorithmic forms have been widely proposed at research and prototype level for around 25 years now, yet they have seen limited deployment in real-life solutions[49]. The IBM Idemix system is reported in the literature as the first project to use (multi-use[50]) anonymous credentials.[51] Since the initial work by Chaum and others, new cryptographic solutions have been designed and tested. These solutions have attempted to fulfil the previously mentioned data minimisation requirements, such as selective disclosure and unlinkability, while also addressing the specific challenges associated with meeting all the other essential requirements of the designed solution. These requirements include holder and device binding and accountability, credentials revocation and credentials delegation (from a trusted issuer to another issuing entity), as well as support for user-friendly digital identity management solutions, primarily for mobile devices. Examples of these challenges include:[52]

- Certain anonymous credentials cannot be directly bound to the secure elements of current mobile devices since they are based on signature schemes that are not supported by the hardware deployed in mainstream mobile devices

- Certain solutions, particularly those enabling the use of any type of signature scheme, may require significant computational resources for the cryptographic generation and verification of credentials.

- Privacy-friendly revocation implementation is a complex challenge that uses specific cryptographic constructs and often requires compromises to achieve an efficient solution[53].

- Non-agility in the use of different cryptographic algorithms (e.g. signature scheme) makes them unfit for change, particularly in view of decryption risks arising from increased computing power and quantum computing.[j]

- Current lack of standardisation for many of the proposed solutions represents an obstacle to widespread real-world adoption.

Recently, scientific literature has proposed many solutions to these challenges, and there have been increased efforts towards standardisation[54]. The debate over the current technical proposal for the EUDIW has accelerated developments, including those from industry.

For example, efforts are being made to further develop BBS/BBS+ signature-based credentials so that they can work with cryptographic primitives that are already accepted by the secure hardware and software currently deployed in commonly used mobile devices.[55] Alternatively, anonymous credentials based on general-purpose zero-knowledge proofs have been proposed, which are able to work with any signature schemes and can cope with many of the aforementioned challenges within an acceptable computational effort[56] . Research is also exploring how to efficiently integrate post-quantum cryptographic primitives into anonymous credentials[57].

While there is a “need for service providers to strike a balance between protocol sophistication, implementation intricacy, and resource constraints” [58], the situation is rapidly evolving and may lead policymakers and service providers towards solutions that do not compromise privacy requirements. The European Telecommunication Standards Institute (ETSI) has issued a technical report[59] which provides “general yet comprehensive analysis of signature schemes, formats and protocols with different degrees of maturity that cater for selective disclosure, unlinkability, and predicate proofs”, with a view to their application in the EUDIW. While describing the current situation and limitations, the report refers to ongoing projects trying to bridge existing gaps.

6. The EU Digital Identity Wallet

The EU Digital Identity Framework and Wallet

Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market (hereinafter referred to as ‘the (eIDAS) Regulation’) was adopted in 2014 to establish a new system for secure electronic transactions between businesses, citizens and public authorities across the EU[60]. The eIDAS Regulation was then amended in 2024 (by Regulation (EU) 2024/1183 hereinafter referred to as ‘the amending Regulation’) to provide a comprehensive EU-wide digital identity framework. It applies to electronic identification schemes notified to the European Commission (EC) by EU countries, to European Digital Identity Wallets (EUDIWs) provided by a Member State as well as to trust service providers established in the EU. The aim is to introduce interoperable EUDIWs across Member States and to remove the barriers to using electronic identification means and trust services in the EU, which were previously based on national legislation and were not interoperable.[61]

Notably, the Regulation requires Member States to provide EUDIWs by the end of 2026.[62] The issuance, use and revocation of these EUDIWs will be free of charge to all natural persons, although their use will not be mandatory. They will enable users to interact with both public and private organisations.

While working on the text of the amending Regulation, the EC adopted a Recommendation[63] calling on Member States to work closely with the Commission to develop a common Union Toolbox comprising a technical Architecture and Reference Framework (ARF),[64] along with a set of common standards, technical specifications, guidelines and best practices for building the EUDIW ecosystem. The EC has been collaborating with Member States[65] and other relevant stakeholders to develop the ARF, starting before the entry-into-force of the Regulation. The EC has also co-funded large scale EUDIW pilot projects,[66] with additional calls for pilot projects launched in 2024 and 2025. Furthermore, the Regulation provides for the EC to adopt implementing acts[67] (not all were adopted at the time of publication of this document) detailing the technical specifications and standards mandated for the EUDIW in a phased approach. The ARF details the requirements that are laid down in technical specifications and in standards, which are then referenced in the implementing regulations. These specifications imply the use of existing standards, with proposals for amendments, and the creation of new standards developed in collaboration with the European Standardisation Organisations.[68] The ARF is developed in an open process on GitHub involving the opportunity for any interested party to provide feedback and input[69].

EUDIW wallet ecosystem and features

For the sake of brevity and focus, we will not be able to provide a comprehensive overview of the EUDIW ecosystem and the features planned. Please refer to the ARF documentation,[70] and more specifically Chapter 3.

The EU Digital Identity framework as an identity model and its sources of trust

The EU Digital Identity Framework can be considered[k] as having some elements of a ‘distributed identity model’, insofar as all Identity Providers (IdPs) satisfying the conditions established by the Regulation may issue personal identity data, attributes and credentials. Furthermore, since the EU Digital Identity Framework is interoperable and cross-border by design, we could consider somehow its model as ‘federated’, since data released by a Member State must be trusted by an RP belonging to another Member State, if the use case provides for this.

The framework integrates an EUDIW that enables the concept of a ‘user-centric’ digital identity paradigm. It also overall enables many of the original SSI principles.[71] At the same time, it differs from the central SSI statement that “the user is the ultimate authority on their identity”. An explanation follows.

For identity data and certain attributes accessed in use cases requiring a high level of trust, for example identification by a law enforcement officer or authorisation to access health or tax services, the ultimate source of trust is usually the relevant EU Member State. Through a chain of trust ensured by the Regulation’s mandated mechanisms and supervised by its established competent authorities, Member States authorise and guarantee the issuance of these identity data, attributes and credentials to EUDIW users in a way that relevant Relying Parties (RPs) can trust. In these use cases, the EUDIW enables users to control their data without granting them ultimate authority.

As to the scope and cross-border acceptance of the EUDIW, Art.5f[72] of the Regulation defines those RPs and relevant use cases where the EUDIW must be accepted as an identification and authentication means. They include:

- public sector bodies providing online public services requiring electronic identification and authentication;

- private companies (except micro and small enterprises), including in the areas of transport, energy, banking, financial services, social security, health, drinking water, postal services, digital infrastructure, education or telecommunications, that are required by law or contract to use strong user authentication for online identification;

- providers of very large online platforms[73] when requiring user authentication to access their services.

For other use cases (for instance fidelity cards, club cards or event tickets) it will be possible for RPs to rely on the use the EUDIW insofar as the overall eIDAS rules are complied with. It will not be possible to manage self-defined attributes that users might want to create on top of the regulated credentials within an EUDIW. Any such applications would need to be managed by a different Digital Identity Wallet.

The EUDIW and personal data protection requirements in the eIDAS Regulation

The European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) has provided formal comments on the original EC Proposal to amend the eIDAS Regulation, as well as on different batches of implementing acts following respective empowerments of to the Regulation. [74] In its remarks the EDPS has highlighted that the success of the EU digital identity framework will be measured not only by its technical capabilities, but also by its ability to genuinely embed and uphold fundamental rights, and specifically data protection. The EDPS has identified the critical junctures in the legislative and technical development process at which it is essential to consider data protection requirements to avoid risks such as widespread surveillance, the ‘wallet as a honeypot’ threat, and the over-sharing of personal data.

In order to mitigate data protection risks, the legislator has included a set of data protection requirements into the amended Regulation throughout the legislative process, gaining increasing attention and leading to gradual improvement. The EC, which during the legislative process had called on representatives from Member States through the comitology instrument[75] to contribute to the EUDIW implementation, has involved other stakeholders, including cryptography experts. Together with civil society, these experts first publicly expressed their views on what they considered insufficient privacy requirements in the proposed Regulation text, and then on what they deemed at that point in time an inadequate practical implementation of these requirements in the implementing regulations,[76] thus contributing towards better results.

Other EU data protection supervisory authorities have also provided feedback on the on-going EUDIW implementation process and on the EUDIW topic. [77]

Data protection related provisions

The eIDAS Regulation aims to establish compliance with the GDPR and a data protection by design approach in several of its provisions. Recital 9 of the amending Regulation highlights that the proposed framework should comply with the GDPR, explicitly referencing the “data minimisation and purpose limitation principle and obligations, such as data protection by design and by default”.

As to the privacy by design approach, the Regulation mandates that the technical framework of the EUDIW:

- not allow providers of electronic attestations of attributes or any other party, after the issuance of the attestation of attributes, to obtain data that allows transactions or user behaviour to be tracked, linked or correlated, or knowledge of transactions or user behaviour to be otherwise obtained, unless explicitly authorised by the user;

- enable privacy preserving techniques which ensure unlinkability, where the attestation of attributes does not require the identification of the user

Specific legal requirements on the EUDIW and other actors of the EU digital identity framework are identified in APPENDIX I.

Measures to implement data protection requirements in the EUDIW

In this section, we describe how and how far the EUDIW provisions and ongoing implementation meet data protection requirements and measures, with a focus on those introduced in chapter 5.

Ensuring confidentiality and integrity

The level of security and trustworthiness in the EUDIW and how it interacts with the other actors of the EU Digital Identity Framework is defined by the concept of ‘level of assurance’ (LoA). This is a term introduced in the eIDAS Regulation that indicates the degree of confidence in a person’s claimed identity when using electronic identification.[78]

The LoAs are classified into three categories: Low, Substantial and High. These categories reflect varying degrees of trust and security in the processes of issuing, verifying, authenticating and managing identities.

The EUDIW has been designed by the legislator to manage electronic identification to the highest security standards. As such, it must comply with High LoA standards to securely store and present ‘qualified attributes’, while ensuring resistance to tampering and cyberattacks. This also implies that the Wallet Unit, the device hosting the EUDIW, must use a Wallet Secure Cryptographic Device (WSCD) to store and manage the cryptographic material used to bind the PID and attributes to the Wallet Unit with a High LoA. We have described the integrity and confidentiality requirements of DIWs in section 5.1, introducing software and hardware features in mobile devices or cloud resources such as Trusted Execution Environments, Secure Elements and Hardware Security Modules, which could provide the required strong security assurance.[79] The WSCD of an EUDIW is to be implemented by adequately integrating these resources.

The implementation of selective disclosure of attributes and unlinkability requirements

We have seen that implementing selective disclosure of attributes and unlinkability requires specific architectural choices for the Digital Identity Wallet (DIW) ecosystem, as well as the use of enabling technologies and protocols. In section 5.2 we discussed the use of anonymous credentials and the cryptographic algorithms that can support these requirements.

An implementing regulation of the EUDIW[80] has established ISO/IEC 18013-5:2021 and ISO/IEC TS 18013-7:2024 as the reference standards identifying the protocols and interfaces for the proximity and remote presentation of EUDIW attributes to RPs. These standards were referred to in section 3.4.

Many in industry and academia[81] have highlighted how using these standards would prevent the development of a comprehensive privacy solution. While they allow selective disclosure, which is already used in smartphones and is being deployed in some national digital driving licence schemes, they do not meet the unlinkability requirements.[82] This is because of the information used when presenting the verifiable credentials to the RP. The presence of unique identifiers in the hashes of user attributes and the IdP’s signatures enables the tracking of multiple transactions with the same RP, as well as further traceability in the event of collusion among RPs, and between IdPs and RPs. One possible mitigation measure would be to use single-use credentials issued in batches. However, this approach introduces challenges related to operational complexity, resource consumption, and credential revocation[83].

This is why some researchers and industry practitioners propose using anonymous credentials and zero-knowledge proofs to meet the unlinkability requirements, while enabling the use of pseudonyms and implementing selective disclosure.

As to revocation related unlinkability, researchers consider it as a hard problem to solve. Some believe that an effective methodology to be applied to anonymous credentials could be similar to the one adopted in ISO/IEC 18013-5:2021. The idea would be to integrate a deadline attribute into a very short validity period, showing the verifier a zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) without disclosing any identifiers and thus not enabling any tracking.

So far, the European Commission has not adopted the anonymous credentials and zero-knowledge proofs solution, reportedly due to limitations regarding its suitability for current mobile devices, the immaturity of the technology, and the absence of standards for implementing it. However, the EUDIW project has boosted developments within industry and standardisation organisations, as we have noted. The European Commission has been carrying out a discussion within the ARF regarding privacy risks and mitigations, as well as relevant technical challenges and solutions, including on zero-knowledge proofs. The aim is to consider a possible future adoption and integration of these solutions into the EUDIW. Within the context of the ARF, the Commission is currently exploring different zero-knowledge-proof solutions by following closely the progress being made in the community of researchers and in the industry on this topic. Furthermore, zero-knowledge proof solutions are currently being tested for the purpose of age assurance in the ‘Age Verification App’,[84] which is being built to the same specifications as the EUDIW. This may also contribute to the further development of these technologies and to boost its adoption in the wallet ecosystem.

One topic of discussion between the EC and other stakeholders has been whether to leave the integration of anonymous credentials for a second phase of the project or postpone the deployment of the EUDIW to start with the right approach. The EUDIW project will have a significant impact in the future of identification and authentication in the digital domain. It will support an increasing number of aspects of our lives and could have wide consequences on our fundamental rights and freedoms. In our view, it is therefore essential to adopt a fully-fledged privacy enabling approach from the outset, even if this implies delaying the project. Alternatively, the architecture of the EUDIW ecosystem should be designed to enable the smooth integration of technologies such as anonymous credentials and zero-knowledge proofs as soon as possible.

Other data protection considerations

Implementing selective disclosure may provide the technical means to decide which information to show RPs within the same credential, but this alone is insufficient for a holistic privacy-by-design solution. The technical and governance architecture should allow RPs to request only what they are lawfully allowed to request and thus prevent them from ‘over-asking’. The legal requirements provide for the obligation for RPs to register what their activities are and the information they may request from EUDIW users. However, at the time of writing this document, there is no obligation for RPs to show EUDIWs in real time the pieces of information they are allowed to request so that the EUDIW user can refuse disclosure; this is merely an option for each Member State to decide. Although other measures could mitigate this risk, the automated interaction between EUDIWs and RPs, coupled with the absence of effective technical controls, could lead to the seamless over-collection of personal data, far beyond the levels we see in current transactions. Furthermore, it is essential to be informed by design of the use cases where RPs are allowed to request the generation of pseudonyms to link multiple transactions, so as to avoid unlawful attempts to profile users. It is also essential to be informed by design of all those use cases where identification is required. This is why a solution should be designed for RPs to systematically provide EUDIWs with this information in real time.

Furthermore, while the current framework integrates certain technically enabled features, it does not mandate a comprehensive consent management solution within the EUDIW. A comprehensive privacy-by-design approach to interactions between EUDIWs and RPs, encompassing all necessary features, is highly recommended for inclusion in the reference architecture and anyhow expected for compliance with the GDPR in any implementation deployed in the EU Member States.

The Regulation, as specified in its implementing acts, provides users of the EUDIW with a function that allows them to easily report an RP to the relevant national data protection authority if they receive an allegedly unlawful or suspicious request for data (including an excessive data access request) from this RP. [l] A better definition of the main use cases of the EUDIW in the different contexts would create a common understanding of the meaning of an excessive data access request, which would be beneficial for users and RPs, and ultimately enhance trust in the EUDIW. Work in this direction is therefore welcome.[85] It will help ensure that data protection authorities do not receive an overwhelming number of reports from users and will facilitate the harmonised use of the EUDIW across the EU/EEA.

7. Conclusion

Digital Identity Wallets are building blocks of future digital identity management solutions as well as the identification and authorisation gateways for our digital transactions, which support an increasing number of interactions in our everyday lives. The aim of these solutions is to provide users with control, security and trust. However, they might also enable tracking and profiling by any potential malicious actors. Furthermore, the success of these solutions depends not only on their features and functionalities but also on citizens’ trust. This is why a data protection by design approach is essential to provide the necessary assurance features while avoiding enabling any possible tracking options. This is not straightforward, especially when considering the need for large-scale deployment in a real-world context. Nevertheless, technological research has made significant progress in reconciling conflicting requirements, and standardisation efforts are increasing. Cryptographers have proposed using anonymous credentials and cryptographic protocols such as zero-knowledge proofs as the main building blocks for a privacy by design and by default solution.